A Taste of the Wild Side

A Taste of the Wild Side

Native Blackberries; Rubus Ursinus

On a farm walk with friends and family this weekend we discovered that many of the native blackberries growing in hedgerows and the understory of our oak woodlands are filled with ripe berries. Unlike the adjacent cultivated field varieties growing in neat domesticated and trellised rows, the native blackberries grow wild among a thicket of other native plants such as Coyote brush, Coffeeberry, Mugwort, Monkey flowers, California Lilac, Sage and many others.

Native blackberries in oak woodland

To pick a handful of these berries may require a series of bends and twists to avoid touching the poison oak or getting pricked by thorns, but it’s worth the effort. Native wild blackberries are a bit more tart and they have a unique bouquet of subtle flavors unlike any of their more domesticated cousins.

Native blackberries and poison oak.

Wild blackberries are never really measured in monetary terms (like price/pound), they are not traded in the marketplace in exchange for paper, they grow wild and are offered freely. As I look down the path where our cultivated patch of blackberries is growing, it strikes me how much of our food production is caught up in the economics of profit and loss, often forgetting to include the value of wilderness in the overall equation.

A happy berry picker.

To gather and taste something that grows wild, uncultivated by any human hand or machine, is a special experience. Most of us are accustomed to thinking of food as a packaged commodity and we forget that the crops we grow have a wild ancestry, which over thousands of years farmers have selected to become today’s food crops.

Cultivated blackberries in rows.

Unlike most of our field crops that grow in rows and straight lines, in nature the general pattern is much more random and chaotic, overflowing with curves, corners, knots, and unpredictable twists and turns. Don’t get me wrong, I love the sight of weed-free “linearity” in the fields, it gives a pleasant sense of controlled organization, and straight rows are testimony to a job well done, especially in front of your fellow farmers. In farming we temporarily trick nature into a predictable pattern, to influence the natural process in our favor so that we can enjoy the beauty and bounty of nourishing foods.

Native blackberries in foreground. Cultivated berries in background.

After picking the wild berries, I walk down the path to taste the first Ollalieberries and it gives me an appreciation of both the wild and the domesticated environments that live side-by-side here on the farm. Both are interdependent and important to manage together.

Cultivated blackberries at top. Native blackberries at bottom.

Reflections on Seasonality and Favorite Crops

Reflections on Seasonality and Favorite Crops

Eating with the seasons teaches us patience. Tomatoes may be available whenever I might want at the store, but few things give me greater pleasure than waiting for that special moment in the season when I can harvest and bite into a sun-warmed, vine-ripened, dry-farmed tomato. Although “dry-farming” sounds ordinary, it is actually the culmination of a complex “dance” between farmer and nature. Dry-farming tomatoes is a technique perfected a couple of decades ago by Molino Creek, a farming cooperative situated in the coastal hills above Davenport. We are fortunate to enjoy a similar microclimate. Dry-farming techniques involve proper spacing, soil moisture control, timely cultivation practices, soil rotation and a number of different fertility practices. Under optimum conditions the plants, although stressed from a lack of water, will stay healthy enough to yield, in my opinion, one of the best tasting red tomatoes out there.

Eating with the seasons teaches us patience. Tomatoes may be available whenever I might want at the store, but few things give me greater pleasure than waiting for that special moment in the season when I can harvest and bite into a sun-warmed, vine-ripened, dry-farmed tomato. Although “dry-farming” sounds ordinary, it is actually the culmination of a complex “dance” between farmer and nature. Dry-farming tomatoes is a technique perfected a couple of decades ago by Molino Creek, a farming cooperative situated in the coastal hills above Davenport. We are fortunate to enjoy a similar microclimate. Dry-farming techniques involve proper spacing, soil moisture control, timely cultivation practices, soil rotation and a number of different fertility practices. Under optimum conditions the plants, although stressed from a lack of water, will stay healthy enough to yield, in my opinion, one of the best tasting red tomatoes out there.

“Early Girl” is the variety of choice for dry-farming; it is one of the very few tomato varieties (possibly the only one) that can be dry-farmed. Bred in France in the 1970’s they became an instant hit when they arrived in the United States and today still rank as one of the most popular tomato varieties, especially among gardeners. Tomatoes are not of European origin, quite the contrary; their ancestry can be traced to the impenetrable jungles of Central and South America. The Mayans called it “xtomatl” hence the name tomato. When the Spanish brought the first tomato to Europe it was given the name “pomodoro” (golden apple) and cursed to be poisonous, like some of its relatives in the nightshade family. It was given the botanical name lycopersicum, which means “wolf peach.” The Church condemned eating tomatoes as a scandalous and sinful indulgence and banned it. On the other hand, the French admired its sensuous appearance and were enticed by it, believing that the red fruit had aphrodisiac powers, and so called it “pomme d’amour” or love apple. Not until the 1800s did the tomato finally gain broad culinary acceptance in Europe. Today, we probably couldn’t imagine anything more scandalous than not having tomatoes as part of our diet.

The crop of tomatoes we are now harvesting was sown in a greenhouse in mid-January and transplanted in the field in March. It takes us over 6 months from planting the seed to finally harvesting the first tomatoes. To extend our harvest into the fall, we add two additional tomato plantings staggered 3 and 6 weeks apart. This is true for many of the 50 or so crops we grow every year; many are planted in succession. Timing, plus adjusting to the variables for each successive crop, is what makes our way of farming uniquely challenging. Successional plantings need to fit natural variables such as soil moisture, temperature, and day length, and synchronize with the timing, field rotations and unique growing habits of each crop variety. Although we are only just starting to harvest our summer bounty of crops, we are already well underway in sowing and planting of fall and winter crops: our winter squash was field sown in June, and will take 100-120 days to mature, so they should be ready sometime in early October; fall and winter leeks were sown in the greenhouse in May and transplanted into the field end of July; other fall crops ready to be planted include the beautiful Romanesco cauliflower, Brussels sprouts and Cabbage. And course popular winter root crops such as parsnips, rutabaga and celeriac (celery root) are being sown now so they have enough time to size up before short cold days stop their growth.

In addition to being patient and flexible regarding “what’s in the box,” CSA members are often asked to be open to trying new types of vegetables. A couple of years ago, for example, we experimented with a new pepper variety – the Padron pepper, and were rewarded with a tasty discovery. Now they have become a staple in our annual production, and will be in the shares with regularity. When my family had this season’s first roasted Padron Peppers a couple of weeks ago, the kitchen filled with that familiar, tantalizing aroma and everyone came to the table with a smile in anticipation of this yummy treat. Even Elisa munched on them, as if the threat of biting into a hot one was of no concern.

In addition to being patient and flexible regarding “what’s in the box,” CSA members are often asked to be open to trying new types of vegetables. A couple of years ago, for example, we experimented with a new pepper variety – the Padron pepper, and were rewarded with a tasty discovery. Now they have become a staple in our annual production, and will be in the shares with regularity. When my family had this season’s first roasted Padron Peppers a couple of weeks ago, the kitchen filled with that familiar, tantalizing aroma and everyone came to the table with a smile in anticipation of this yummy treat. Even Elisa munched on them, as if the threat of biting into a hot one was of no concern.

No one has written a more poetic and humorous story about these Padrons than our neighbor-farmer Andy Griffin, of Mariquita Farm. If you love these peppers as much as I do then you owe it to yourself to read his story, “Pardon my Padróns.” Andy is always one-up on his fellow organic growers when it comes to experimenting with and selecting unusual and great tasting vegetable varieties. So thanks to Andy, and subsequent requests by CSA members and farmer’s market customers, we started growing “Chiles de Padron.” The Padrons are said to have been brought to Spain from Mexico by Franciscan monks in the 16th century, where they were then adapted to the soils and climate of Galicia near the town of Padron, after which the Peppers are named. The town of Padron is located near the Atlantic coast, where today they are grown extensively in a climate probably very similar to ours. The people of Padron best describe the character of these peppers in their native Galician as “Os pementos de Padron, uns pican e outros non.” (Padron peppers, some are hot and some are not.) Indeed, eating Padron peppers is likened to playing Russian Roulette — you never know which one you bite into will be burning hot. Debbie offered to include her description of how they are best prepared. So enjoy, but don’t forget to have something close by to cool your palate should you encounter a hot one!

Tomatoes (Pomme d’Amour) – the Summer Fruit Everyone Loves

Tomatoes (Pomme d’Amour) – the Summer Fruit Everyone Loves

These last two Saturdays we enjoyed an amazing turnout of people eager to pick their own tomatoes. I am not exaggerating when I say that a couple of tons got picked. Tomatoes were carried away in buckets, carts (Radio Flyers), boxes, bags, coolers and wheelbarrows. I would love to have followed the trail from our fields into peoples’ kitchens, to see how these beautiful summer fruit were being preserved — chopped, sliced, blanched, skinned, boiled, dehydrated, or roasted — for Fall and Winter use. Pickers also explored the surrounding fields, harvesting a diversity of other tasty crops such as our “toe-curling” Sungold cherry tomatoes, peppers, sweet berries, crunchy apples… even sunflower-heads filled with tasty seeds and spicy daikon radishes were taken home by some adventurous harvesters.

Events like these always reaffirm my belief that a farm is more than just a place that grows and sells food. It’s a place where community can enjoy the simple pleasures of picking and eating something right from the field where it is grown and cared for, surrounded by nature. We spend so much time talking about food justice, food security, food safety, food nutrition, food systems… yet that which gives vitality and meaning to the land’s nourishing gifts – food pleasure – is often overlooked. The pleasure we find in food is contagious and speaks to the farmer within us, the one that believes in growing flavorful, fresh, and nourishing food. It speaks to the cook in us who enjoys preparing a delicious meal, and of course it speaks to us eaters (that’s everyone), who undeniably take pleasure in eating and sharing a delicious meal.

Personally, few things give me greater pleasure than to pick and eat something right in the field, whether it’s a bright red gala apple, a juicy red dry-farmed tomato, a crunchy green bean, or a sun-warmed ripe berry; it is such a simple but deeply satisfying experience. The pleasure we get out of great tasting food is sometimes not acknowledged enough. The guiding principle of our farm is to maintain that intimacy and openness between farm and community, such that we can all experience the pleasure of this nourishing relationship.

Personally, few things give me greater pleasure than to pick and eat something right in the field, whether it’s a bright red gala apple, a juicy red dry-farmed tomato, a crunchy green bean, or a sun-warmed ripe berry; it is such a simple but deeply satisfying experience. The pleasure we get out of great tasting food is sometimes not acknowledged enough. The guiding principle of our farm is to maintain that intimacy and openness between farm and community, such that we can all experience the pleasure of this nourishing relationship.

Enjoy these last few weeks of summer and come out to the farm while tomatoes are still plentiful. You are welcome to pick by yourself during our regular Saturday Farm stand hours between 10am-3pm. Another great opportunity to enjoy and support the farm is during our upcoming events. The Live Earth Farm Discovery Program’s Fundraiser is on September 22nd, a not to be missed, in-the-field Culinary Feast; there’s also an Apple U-pick and Fresh Cider Pressing Community Farm Day on September 29th, and our End-of-Season Harvest Fest on October 20th.

Hope you can all come and enjoy “YOUR” Farm.

The Farmer and Gardeners Hidden within Us All

The Farmer and Gardeners Hidden within Us All

At 91 years of age my mother’s love for and excitement about growing plants has not diminished, even though her gardening space is now reduced to the sunny side of a small apartment. When I visited my parents last week, she proudly showed me her first tomatoes, picked from her three tomato plants growing in large pots in a corner of her terrace. Her “garden” this year consists of a couple planter boxes of her favorite herbs and salad greens, and I wasn’t surprised to see the balcony outside her kitchen bursting with colors from her favorite flowers.

When I was growing up, the kitchen and garden were always closely connected; my favorite place to play was right outside the kitchen door. I was lucky enough to enjoy the company of several domesticated animals including chickens, dogs, parrots, guinea pigs, and rabbits. We had a large eucalyptus tree with a tree house to climb around in. We also had many different fruit trees, so I could harvest and eat directly from the garden to my heart’s content. Hedges, shrubs and a vacant lot adjacent to our garden provided the “wild” exciting places for me to explore and hide in. I always liked helping my mother in the garden, especially sowing seeds and then eagerly waiting for them to germinate. Harvesting something from the garden was always special as well, and I loved bringing the things I picked into the kitchen where they would then be cleaned and prepared into a dish for the next meal or preserved for later use. Our garden was like a little sanctuary, a place to play and spend time with friends and family; there’s no question it inspired my later interest in farming. In some ways Live Earth Farm is an extension of that childhood experience — a place with an abundance of plants, animals and diverse landscapes where community is built around growing healthy seasonal fruits and vegetables, and transforming the harvest into meals shared with family and friends is a natural extension of the process.

A little over a hundred years ago, agriculture was not only the major source of income in this country, it was the center of every community, providing sustenance, social interaction, and lively mealtime conversations around the dinner table. In the early 1900’s more than 30% of the US labor-force were farmers. Today the U.S. census has stopped counting farmers since only 2% of the workforce — less than a million people — are farmers. It seems like we’ve reached an extreme, where the majority of the population buys their food in the supermarket (much of it processed, with little evidence of its source). But this “fast food” mentality is starting to crumble; many people are again making the conscious link between nutrition of our bodies and the health of our environment. One indicator is that all across the country there is a resurgence in gardening, focused on growing food at schools, in vacant lots in and around urban centers, at home… even the White House has an (organic!) vegetable garden, which is supplying the First Family’s kitchen. This popularity in gardening of course has its many reasons. Motivations include the desire to improve our diet, to enjoy fresher and better tasting fruits and vegetables, for convenience, to learn to cook with the seasons, to lower grocery bills, to create time to spend with the family… sometimes it is just done for the sheer pleasure of growing something and/or bartering/sharing the surplus with friends and neighbors.

Although the ‘less than 2% of US population is a farmer’ statistic — combined with the average age of today’s farmer being over 55 — is alarming, there is evidence that it’s not due to a lack of interest in farming. According to a recent article published by Cornell’s Small Farm program, one of the most popular video games on the market is called “Farmville”, with over 80 million people here in the United States currently signed up and playing it. That is amazing… 80 million people! This just shows that the interest in farming is alive and well, that there is a farmer or gardener hidden somewhere in all of us, even if only in the “cool” world of virtual farming. Suddenly I can see Community Supported Agriculture turning into a movement, where knowing your farmer, growing your own, and/or going to farmers markets is mainstream, the norm. (Farmers market attendance alone has doubled from 2011 to 2012.) I am sure this is possible, that a much larger percentage of people will be more passionate and excited about farming for real. It might just be the trend of the future, who knows?

For the last 16 years we have offered young people the opportunity to experience what life on a farm is like, by providing the hands-on experience of running a farm, from planning and organizing to growing, harvesting, selling and delivering quality produce to the community. Many apprentices have moved on to start their own farms or engage in careers that help build sustainable food systems. Live Earth Farm’s Discovery Program hosted more than 1400 children last year, using the Farm as a classroom to teach field-to-fork environmental stewardship. The farm is an ideal venue for teaching about where our food really comes from, and for learning about the interconnectedness between humans and the larger natural ecosystem. As CSA members and friends of the farm, your commitment and financial support have been essential to the strength and development of the farm’s educational efforts.

I would like to encourage everyone to support us this year so we can expand our programming and outreach and continue to inspire the next generation of young farmers and gardeners. If you haven’t done so yet, I want to invite you to get your tickets now for one of the farm’s most memorable annual events: our annual fundraiser dinner. This year, “DIG”, the in-the-field dinner (September 22nd – details below) will be in an amazing setting here on the farm, with incredible food and entertainment. The best part, though, is that all of the proceeds will go to inspire the next generation of new farmers and gardeners growing food directly in and for their communities. I hope you can join us!

Below, farmers of all ages at Live Earth Farm, from kids working in the Discovery Garden, to trying their hand at milking a goat, to apprentices learning how to use a tractor; at bottom are Jeff and Anna, last year’s “Young Farmer” team, who have since married and gone off to start a farm of their own…

Summer to Fall – When Seasons Collide

Summer to Fall – When Seasons Collide

We are now officially in our last week of Summer. September 21st marks the Autumn Equinox, and the beginning of fall. It is an odd time of seasonal overlap; we are reaching the peak of the Summer season harvest-wise, yet the foliage on plum trees and native poison oak is changing to red, the daily number of eggs collected are dropping and pumpkins are turning orange. Everyone working on the farm has turned into an “acrobat” juggling a larger number of tasks than usual. Nothing is more telling of this seasonal transition, however, than when we are fully immersed in our apple harvest. Trees hang heavy with beautiful green, yellow, orange, and red, apples. Gala’s are at their peak of ripeness. Harvest bins line the orchard floor, some empty, others filled to the brim. Filled bins are hauled out – some get sorted and washed for immediate use, while others go into cold storage to be sorted and processed later.

We are now officially in our last week of Summer. September 21st marks the Autumn Equinox, and the beginning of fall. It is an odd time of seasonal overlap; we are reaching the peak of the Summer season harvest-wise, yet the foliage on plum trees and native poison oak is changing to red, the daily number of eggs collected are dropping and pumpkins are turning orange. Everyone working on the farm has turned into an “acrobat” juggling a larger number of tasks than usual. Nothing is more telling of this seasonal transition, however, than when we are fully immersed in our apple harvest. Trees hang heavy with beautiful green, yellow, orange, and red, apples. Gala’s are at their peak of ripeness. Harvest bins line the orchard floor, some empty, others filled to the brim. Filled bins are hauled out – some get sorted and washed for immediate use, while others go into cold storage to be sorted and processed later.

Everyone visiting the farm loves the experience of picking and eating apples directly from the trees or using the farm’s cider press to crush and press the freshly harvested apples into delicious sweet cider. Few experiences are more satisfying to me than biting into a fully tree-ripened apple; it is yet another pleasure of experiencing our relationship with the nourishing cycle of nature. If you’re not a farmer though, you probably are not aware of what all goes into producing that sweet, crisp fruit. An apple orchard needs year-round attention, and the perennial cycle is very different from the annual, season-focused vegetable crops we grow. Apples lean heavily on human help and it takes a lot of devotion, from winter pruning through post-harvest cleanup in late Fall.

Apples thrive in our climate. One wouldn’t think by driving through the Pajaro Valley that this was once one of the largest apple growing districts in the country. Most of the apple orchards have been pushed over by bulldozers, replaced by the more lucrative berry, vegetable and flower crops. The predominant variety then was the Newtown Pippin, a variety originally from New York, introduced by settlers in the 1850s. Today it is still the trademark apple in Martinelli’s popular apple juice, processed here in Watsonville, and probably the reason why Newton Pippins are still grown commercially in this area.

Here on the farm we grow approximately 7 acres of apples, mostly Fuji, Gala, Sommerfeld and a few Newton Pippins. Starting in winter, the dormant season, trees first have to be pruned, and then sprayed with oils or sulphur before and after budbreak to fend of insect and fungal diseases. Pheromone wires have to be tied to the trees at a precise time in the spring to confuse the mating cycle of codling moths which will greatly reduce worms from hatching and burrowing into the apples. Once the soil dries the orchard needs to be cultivated, both to control weed competition and trap valuable winter moisture in the ground. In April, beehives are brought in to ensure good pollination and after a successful fruit set, the entire months of May and part of June is spent hand thinning trees to ensure fruit will develop into a marketable size. The first seasonal watering happens sometime in June and propping up branches to support the increasing weight load of the fruit is critical during the early summer months.

Here on the farm we grow approximately 7 acres of apples, mostly Fuji, Gala, Sommerfeld and a few Newton Pippins. Starting in winter, the dormant season, trees first have to be pruned, and then sprayed with oils or sulphur before and after budbreak to fend of insect and fungal diseases. Pheromone wires have to be tied to the trees at a precise time in the spring to confuse the mating cycle of codling moths which will greatly reduce worms from hatching and burrowing into the apples. Once the soil dries the orchard needs to be cultivated, both to control weed competition and trap valuable winter moisture in the ground. In April, beehives are brought in to ensure good pollination and after a successful fruit set, the entire months of May and part of June is spent hand thinning trees to ensure fruit will develop into a marketable size. The first seasonal watering happens sometime in June and propping up branches to support the increasing weight load of the fruit is critical during the early summer months.

Then it’s time to prepare for harvest: bins needs to be placed among the trees in the orchard rows, and from early September until late October we hope to be rewarded with a high percentage of beautiful fruit. As soon as the fruit is harvested and windfalls are picked off the ground, it’s a race against time to prepare the orchard for the wet winter months ahead, spreading lime, gypsum and compost, collecting the propping stakes and tying them to the trees, and sowing a cover crop of barley and vetch.

For a brief while longer we can ignore all the early Halloween merchandise and enjoy our summer treats as nature changes into her colorful autumn dress. On the farm, a stand of blooming sunflowers are tilting their giant heads towards a row of yet-to-be-picked Newton Pippins, as if anticipating the seasonal change. The energy in plants is starting to move toward the roots and seeds, and leaves are falling as their life forces go within. By eating with the seasons, we participate in this journey with all other living organisms we share this planet with. Happy Fall Equinox to all of You!

When Seasons Collide – Redux

When Seasons Collide – Redux

With October here, our Coastal Summer has arrived… but will it last? Late season heat waves are not uncommon, but for coastal growers like us, spoiled by year-round moderate temperatures — when yesterday’s thermometer hit a blistering 100 degrees it was a scramble to adjust irrigation, planting and harvest schedules to deal with it. Growing a diversity of crops is always a mixed blessing; some thrive, while others get stressed. Tomatoes, peppers, green beans and squash will get a late season boost from the heat, but ripening apples and berries may get sunburned. And insects, especially aphids and flea beetles which thrive in warm weather, will probably multiply on some of their favorite host crops (cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, broccoli) which have already been planted for late fall and winter harvest. Fortunately this time of year there are plenty of beneficial predator insects which will help keep the population of aphids down. We also use physical barriers to limit pest incursion, such as putting floating row cover over the young and more vulnerable arugula and Brussels sprouts. By week’s end this heat wave will be a distant memory, as the first chance of showers for our area is predicted. If it materializes, it will quench a very thirsty, dry landscape.

With October here, our Coastal Summer has arrived… but will it last? Late season heat waves are not uncommon, but for coastal growers like us, spoiled by year-round moderate temperatures — when yesterday’s thermometer hit a blistering 100 degrees it was a scramble to adjust irrigation, planting and harvest schedules to deal with it. Growing a diversity of crops is always a mixed blessing; some thrive, while others get stressed. Tomatoes, peppers, green beans and squash will get a late season boost from the heat, but ripening apples and berries may get sunburned. And insects, especially aphids and flea beetles which thrive in warm weather, will probably multiply on some of their favorite host crops (cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, broccoli) which have already been planted for late fall and winter harvest. Fortunately this time of year there are plenty of beneficial predator insects which will help keep the population of aphids down. We also use physical barriers to limit pest incursion, such as putting floating row cover over the young and more vulnerable arugula and Brussels sprouts. By week’s end this heat wave will be a distant memory, as the first chance of showers for our area is predicted. If it materializes, it will quench a very thirsty, dry landscape.

Looking ahead, the winter squash is stellar and I predict we’ll have a bumper harvest of four of my favorite types: Delicata, Butternut, Kabocha (pictured at right), and Sweet Dumplings — all great to cook with. The pumpkins are also quickly turning bright orange, just in time for our harvest celebration (see announcement). The concord grapes are sweet and fragrant and so are the Quince. Fields are being prepared for end-of-season plantings of strawberries, garlic, onions, artichokes and cover crops. October is always a time of seasonal transition; we are holding on to the last of our summer crops, the Newton Pippin and Fuji apple harvest is in full swing, apricot trees need to be pruned, winter squash needs to be harvested… we all feel a little nervous as the season slowly turns and the chance of early storms, announcing the beginning of the rainy season, is not far off.

Looking ahead, the winter squash is stellar and I predict we’ll have a bumper harvest of four of my favorite types: Delicata, Butternut, Kabocha (pictured at right), and Sweet Dumplings — all great to cook with. The pumpkins are also quickly turning bright orange, just in time for our harvest celebration (see announcement). The concord grapes are sweet and fragrant and so are the Quince. Fields are being prepared for end-of-season plantings of strawberries, garlic, onions, artichokes and cover crops. October is always a time of seasonal transition; we are holding on to the last of our summer crops, the Newton Pippin and Fuji apple harvest is in full swing, apricot trees need to be pruned, winter squash needs to be harvested… we all feel a little nervous as the season slowly turns and the chance of early storms, announcing the beginning of the rainy season, is not far off.

– Tom

No Place Like It

No Place Like It

Last week on July 4th, I celebrated Independence Day in an unusual manner. Having just finished packing shares for Thursday’s delivery, I went on my first ever whale watching adventure, right here in Monterey Bay. Now I easily get seasick, so I never would have initiated an outing like this, however our good friends Miriam and Harley Goldberg learned that blue whales were being sighted in the Bay, jumped on some reservations, then convinced me to leave with them on a boat from the Moss Landing Harbor, a mere 20 minutes from the farm. Armed with candied ginger and a special anti-seasickness wristband we headed into the Bay. We weren’t out long before we spotted a huge vertical water spout, followed by the smooth long blue-grey ridge of a whale’s back. The moment was brief; the whale broke the water’s surface, gliding effortlessly, then disappeared again. Shortly after the first spout we spotted another… equally impressive, easily 20 ft high. The marine biologist on board confirmed these were two adult blue whales, actively feeding on their favorite food: krill, a small shrimp-like zooplankton, currently abundant in the nutrient-rich cold water upwelling from the deep marine canyons of Monterey Bay. It’s rare, we were told, to see blue whales so close to shore. As we followed these giants for the next hour, surfacing every 5-10 minutes for a breath before plunging down to scoop up more krill, I thought about just how amazing this all was. First, that I wasn’t getting sick; second – and more importantly – realizing how fortunate I am to be able to farm in such close proximity to these rich ocean waters — unique, in that their moderating effect on our coastal climate is what allows us to grow such a diversity of crops year-round. The Monterey Bay really is one very special ecosystem, a region where land and ocean are intricately linked, offering up an abundance of rich, nourishing food.

Last week on July 4th, I celebrated Independence Day in an unusual manner. Having just finished packing shares for Thursday’s delivery, I went on my first ever whale watching adventure, right here in Monterey Bay. Now I easily get seasick, so I never would have initiated an outing like this, however our good friends Miriam and Harley Goldberg learned that blue whales were being sighted in the Bay, jumped on some reservations, then convinced me to leave with them on a boat from the Moss Landing Harbor, a mere 20 minutes from the farm. Armed with candied ginger and a special anti-seasickness wristband we headed into the Bay. We weren’t out long before we spotted a huge vertical water spout, followed by the smooth long blue-grey ridge of a whale’s back. The moment was brief; the whale broke the water’s surface, gliding effortlessly, then disappeared again. Shortly after the first spout we spotted another… equally impressive, easily 20 ft high. The marine biologist on board confirmed these were two adult blue whales, actively feeding on their favorite food: krill, a small shrimp-like zooplankton, currently abundant in the nutrient-rich cold water upwelling from the deep marine canyons of Monterey Bay. It’s rare, we were told, to see blue whales so close to shore. As we followed these giants for the next hour, surfacing every 5-10 minutes for a breath before plunging down to scoop up more krill, I thought about just how amazing this all was. First, that I wasn’t getting sick; second – and more importantly – realizing how fortunate I am to be able to farm in such close proximity to these rich ocean waters — unique, in that their moderating effect on our coastal climate is what allows us to grow such a diversity of crops year-round. The Monterey Bay really is one very special ecosystem, a region where land and ocean are intricately linked, offering up an abundance of rich, nourishing food.

There I was, seemingly only moments ago, on land, at the farm, packing CSA shares; then I was standing on the bow of a boat, watching the largest animals ever known to have lived on our planet scoop up tons of krill in one of the world’s richest and most diverse marine environments – the Monterey Bay Marine Sanctuary. In farming, we easily get caught up in the economics of food production, often ignoring the importance of balancing the diverse relationships between the cultivated and non-cultivated environments around us. Here on the farm our fields are surrounded by native habitat, plants and animals; the boundaries between domesticated land and wilderness are easily blurred. Most of the time this means we are a source of food for a diverse community of living creatures (humans included), a community I like to believe can coexist. It also means sometimes we have deer munching on our green beans, coyotes catching a few of our chickens or birds pecking on our fruit.

Just like the Monterey Bay marine environment needs protecting, so too do the rich agricultural lands surrounding the Bay need protecting – primarily from encroaching urban development. Well managed ranches and farms are vital to helping support wildlife habitat, healthy soils, local food supplies, and recreational and scenic resources. Equally important is that agricultural land be protected, so that future generations of family farmers and ranchers can continue farming and support a healthy local economy based on healthy ties to the land and their agrarian values. So thank you all for supporting this farm, as well as so many other local farmers and producers who supply us with their locally grown crops and farm products. It makes our work so much more meaningful. I like to believe that food is a vehicle for creating a more secure and stable future, one where we celebrate our interdependence rather than our independence.

Happy belated 4th of July – Tom

Seeds of Change: Our Food Chain in Peril

Seeds of Change: Our Food Chain in Peril

In nature it is inconceivable that genetic material (DNA) from one organism is inserted into a different species. Imagine exchanging genes from a rat or fish with those of a tomato. This is nothing unusual, however, with today’s DNA technology. GMO corn and soybeans, for example, are grown on millions of acres across the country, largely unchecked as to whether they are harmful to the environment or human health. As with any life form, once established in its new surroundings, it can replicate, change and spread. The genie is out of the bottle now, difficult or impossible to stuff back.

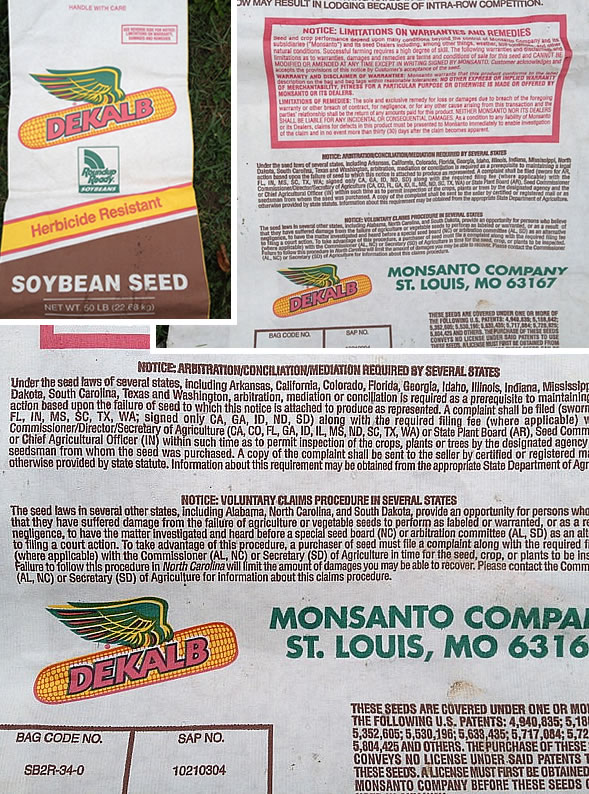

In nature it is inconceivable that genetic material (DNA) from one organism is inserted into a different species. Imagine exchanging genes from a rat or fish with those of a tomato. This is nothing unusual, however, with today’s DNA technology. GMO corn and soybeans, for example, are grown on millions of acres across the country, largely unchecked as to whether they are harmful to the environment or human health. As with any life form, once established in its new surroundings, it can replicate, change and spread. The genie is out of the bottle now, difficult or impossible to stuff back. sold in grocery stores in California, just like they’re labeled for consumers in over 60 countries around the world (see typical EU label, at right). Big pesticide companies are spending one million dollars a day to confuse California voters about Prop 37. Monsanto and DuPont are the biggest donors, with BASF, Bayer, Dow and Syngenta amounting to over $20 million. Another nearly $20 million is coming from PepsiCo, Nestle, CocaCola and friends. Corporate greed and economic profiteering, not the common public good, is behind the no-vote for Proposition 37.

sold in grocery stores in California, just like they’re labeled for consumers in over 60 countries around the world (see typical EU label, at right). Big pesticide companies are spending one million dollars a day to confuse California voters about Prop 37. Monsanto and DuPont are the biggest donors, with BASF, Bayer, Dow and Syngenta amounting to over $20 million. Another nearly $20 million is coming from PepsiCo, Nestle, CocaCola and friends. Corporate greed and economic profiteering, not the common public good, is behind the no-vote for Proposition 37.

Seasonal Transitions

Seasonal Transitions

“The senses can become tools of choice, defense, and pleasure; they give new ‘sense’ to our actions in the field.” – Carlos Petrini, from his book Slow Food Nation.

Call me a sun-worshipper I have always been fascinated by the photosynthetic intelligence of plants, turning light into life. I wouldn’t have a job if it weren’t for this amazing miracle of nature. Plants capture the energy transmitted by the sun, add water, minerals, and CO2 and – viola, we have the fundamental ingredients to live another day – food and oxygen.

I like the nourishing abundance that comes with long, warm summer days. This morning when I dropped off my daughter, Elisa, for her first day back to school, I noticed a hint of sadness knowing a seasonal transition is just around the corner – shorter days, shifts in weather patterns, the leaves turning colors. I am sure the foggy, overcast, drizzly morning didn’t help. As I head back to the farm I inspect the last planting of a new block of tomatoes and peppers just starting to mature. Secretly I wish for a warm and dry Fall to stretch late into November. I am torn – I know we desperately need the rain.

Don’t Miss it! Last Tomato U-Pick of the season!

Before the change in seasons get’s us by surprise, this Saturday is a great opportunity for all who haven’t yet made it out to the farm to load up on sweet, delicious dry-farmed tomatoes. Just think of the pleasure of opening a jar of tomato sauce when you prepare a meal this upcoming winter season.

Hope to see you all here this Saturday, picking and having fun on the farm.

Camphill Communities California thanks Live Earth Farm for their generous and abundant weekly contributions of fresh, delicious organic fruit and vegetables for the hungry mouths of our growing community in Soquel California.

Camphill Communities California is a 501(3)c organization serving adults with developmental disability. Our mission is to provide a nurturing and dynamic residential community where adults with special needs work, learn and live together with professional caregivers and volunteers.

With more than 7 acres of land, Camphill California has a year-round agricultural and horticultural program that includes organic vegetable, herb and flower gardens, a vineyard, and an orchard. Although our gardens supply a portion of our produce, weekly donations from Live Earth Farm provide an additional and important source of fresh, organic fruits and vegetables for our food production workshops, weekly community café, and for our seven homes.

Each week, Camphill California volunteer program coordinator, Ala Jacob, a Live Earth Farm CSA member for six years, loads up her car with eight crates of fresh, delicious vegetables and fruits for our hungry community. Then Ala and her food processing team turn Live Earth Farm vegetables into kimchi, sauerkraut, chutneys, pickled vegetables, tomato sauce and jam.

An additional use of our wonderful Live Earth Farm harvest is our Wednesday lunch café. Each week our five-member cooking team transforms the Farm’s fresh, delicious produce into a mouth-watering hot lunch for our community of nearly fifty.

Thank you Live Earth for supporting the local community with your generous donations!